Chinese Urban Landscape

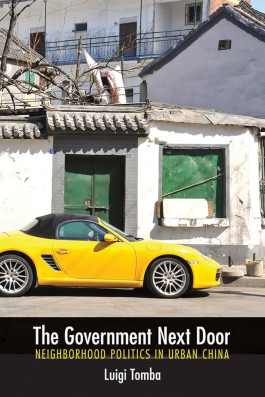

BAM co-founder Jake Walker’s essay presents a critical exploration of the Chinese urban landscape and public realm, contrasting it with American perspectives on urbanism. Through a focus on concepts like American exceptionalism, mythology, leisure, and China’s unique socio-cultural constructs, Walker critiques biases in Western urban discourse and discusses how China’s evolving urban environment embodies distinct cultural, historical, and political dimensions, arguing for a more nuanced approach that acknowledges the complexities of Chinese urbanism without imposing Western frameworks. Through this lens, the article aims to illuminate the unique sociocultural dynamics that define China’s evolving urban environments.

Misfortune may give rise to blessing, but may also hide within it.

— Laozi

THE CHINESE URBAN LANDSCAPE AND PUBLIC REALM

This article is intended to provide a unique perspective on the Chinese urban landscape and public realm. Here the definition of the Chinese urban landscape and public realm is framed through a contrasting and argumentative position on the American discourse on the public realm and urban spaces. My critique of the American lens is aggressive, and frankly a discussion of the Chinese urban landscape and public realm warrants an approach that does not attempt to compare one condition to another. As such, the chapter of this article dedicated to the American lens, which is knowingly conflated with the topic of American Exceptionalism, could be entirely omitted. Removing this polemic would not only produce a more concise and pointed account of the Chinese urban landscape but also avoid potentially contentious topics and clearly represent a ‘safe’ approach. However, when considering the removal of an address of American Exceptionalism, I fear a visceral impulse would be lost in the position taken, and given this article is not the conclusion of a potential direction of research but instead closer to a beginning, I believe there exists a value in attempting to thread together disparate considerations.

While the focus of this writing is primarily aimed at the larger scale and more ‘universal’ discourse related to urban sociology, design, and planning theory, a latent secondary concern exists local and specific to the pedagogy of elite institutions for higher education and specifically Harvard. At the scale of the discourse, if a balanced definition of the Chinese urban landscape and public realm is to be arrived at and communicated, there first needs to be a recognition of the biases inherent when viewed from a framework established to address the American context and discourse. The recognition of potential biases must be accompanied by attempts to dismantle them to reconstruct the perceptive framework to allow for definitions of the public realm to exist beyond a discourse that frames the American context as exemplary.

Being for, by, of, or in the public is fundamentally a dialectical construct in which a definition of self implies reciprocity through which the non-self is also defined. The meaning of what the ‘public realm’ is also transforms through the evolution of the definition of the ‘private realm.’ Therefore, to understand and discuss the sociological characteristics of the public, one must also grapple with the ethnographic dimension of self. Therefore, in an attempt to problematize American exceptionalism in the discourse of the public realm, the complex interrelation of democratic values, identity politics, capitalism, and the Anglo-Saxon myth become a vast territory for deconstruction. Fundamentally such deconstruction is not intended to be purely argumentative but intends to establish or induce a cultural ‘reformatting’ which often naturally occurs when one is a transplant from one culture to another. The intention is to break down the common, familiar, and typically unquestionable to allow space for the redefinition on other terms. American Exceptionalism is so deeply ingrained that any attempt to address it or strip it away from discourse results in a bewildering quagmire of hypothetical, causal, and synchronistic relationships. Even so, here exists an attempt to address the relationship of American democratic values, predatory capitalism, and self-centered identity politics, as a manifestation of American Exceptionalism which, if left unaddressed, produces a bias through which the rest of the world is understood to lack potential for substantive contribution to a discourse on social equity and urbanism.

The general arc of the argument with regards to problematizing the American outlook attempts to link a righteous religious mandate as a nation chosen by God with a capitalist impulse that predates and continues to override the establishment of a unified ‘social contract.’ The sentiment could not be better exemplified than by the words of one of the world’s greatest capitalists John D. Rockefeller.

God gave me my money. I believe the power to make money is a gift from God … to be developed and used to the best of our ability for the good of mankind. Having been endowed with the gift I possess, I believe it is my duty to make money and still more money and to use the money I make for the good of my fellow man according to the dictates of my conscience.1

Following this thread of America’s divine capitalism eventually leads to an understanding that contemporary consumer culture is primarily driven by a desire for ever-heightening degrees of individuation expressed through ‘identity’ as defined through the purchase of consumer goods. The American predisposition to a political discourse centered on identity is not exclusively arising from a call to social justice and equity but potentially more so a result of being ideal for capitalist-driven consumerism. The flourishing of consumerism places undue pressure on democratic values, which in principle, are based on the idea of the public as active citizens instead of passive consumers. Instead, the democratic system capitulates and is ultimately warped by consumerist practices in which the general public does not choose a form of governance based on policy or capability of representatives but instead through the reflection of self-image, which most closely aligns with one’s own identity and values. The precarity of American democracy as ideal grounds for American capitalism as manifest through consumable individual identity is an attempt to expose participatory values as a veil for underlying power structures. The hope would be that in recognizing these ‘facts’, one would be willing to allow for the construction of a definition of the individual-public dualism, which moves away from the overcharged political dimension posed by the American public discourse.

After taking issue with American exceptionalism as manifest through proclaimed democratic values deniably hijacked by capitalism, a more balanced and comparative approach is taken to establish a definition of the Chinese public realm, focusing on three characteristics, mythology, leisure, and the cultural propensity for change. While the characteristics of mythology and leisure in the urban landscape are unique in their own right, the topic of a culture primed for and practiced in rapid change attempts to bring full circle the importance of an examination of the Chinese urban landscapes in terms unfamiliar to western urban socio-political and analytical discourse. Regardless of where American values lie, the technological, economic, and political rise of China has the potential to construct a world order which is not only unfamiliar to American value systems but will inherently be viewed as a threat given America’s underlying mandate from God. The very real potential for conflict elevates the importance of a greater understanding of uncomfortable and potentially threatening territories.

PROBLEMATIZING THE AMERICAN DISCOURSE ON PUBLIC REALM

The context of this writing must first be understood as an all-consuming polemic arising from observations in navigating the process of professional practice in designing urban landscapes in China.

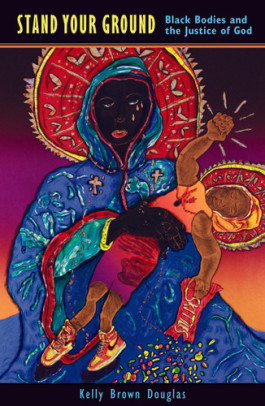

In Kelly Brown Douglas’s Stand Your Ground: Black Bodies and the Justice of God, she expertly unravels the history of American exceptionalism with its roots in the construction of the Anglo-Saxon myth during the English Reformation in the 15th century when splitting from the catholic church. The Anglo-Saxon myth, constructed in opposition to Roman Catholicism, is heavily rooted in a morality granted through a combination of divine right and bloodline. “To be an Anglo-Saxon nation is to be a chosen nation. It is this constructed racial-religious synchronicity that makes America exceptional.”2 Given the foundational aspect of the Anglo-Saxon myth in the American psyche, the resulting form of exceptionalism reformulates issues specific to America as global while also placing itself at the fore of discourse and solutions. While Douglas examines this lineage of American exceptionalism through the racial conflicts of present-day America, wider ramifications exist when considered in the global context.

While most contemporary understandings associate America’s exceptionalism with its form of democratic governing and its mission to spread democratic principles across the world, to understand it as simply about politics and mission does not capture the racial or divine character of America’s narrative of exceptionalism.3

Much of the progressive discourse arising from America concerning urbanization and the public realm is a field of paradoxical landmines. One such condition is the unavoidable and unfortunate fate of a discourse framed through the lens of equity and politics in which, no matter how well-intentioned or inclusive the intention is, positions will inevitably be unaccounted for or marginalized. In liberal discourse and associated planning theories, American exceptionalism is neither overt nor intentional, yet it has an inherent, unavoidable bias that contradicts the progressive agenda. It was not the initial intent to become fixated on accounts of American exceptionalism; however, the recollection of experienced counterpoints from over a decade of living in China was unavoidable. However, subtle American exceptionalism seems pervasive in constructing a discourse on the public realm. Therefore, any line of inquiry on the public realm focusing outside of the United States which does not initially problematize the American lens will continue to proselytize American values as global.

The traces of American exceptionalism lightly peppered through the contemporary framing if the discourse on the public realm could potentially be overlooked, however with the overriding theme of justice as the central component to a definition of the public realm, it invites a problematic trajectory in which the idea of justice concerning the American urban context is viewed as universal and should therefore be applied everywhere, in the same way, across the globe. It is not unlike the messaging associated with American democracy in which the idea of American democracy becomes more important than the reality of how it functions.

Americans may be encouraged to vote, but not to participate more meaningfully in the political arena. Essentially the election is a method of marginalizing the population. A huge propaganda campaign is mounted to get people to focus on these personalized quadrennial extravaganzas and to think, “That’s politics.” But it isn’t. It’s only a small part of politics. The population has been carefully excluded from political activity, and not by accident. An enormous amount of work has gone into that disenfranchisement. During the 1960s the outburst of popular participation in democracy terrified the forces of convention, which mounted a fierce counter-campaign. Manifestations show up today on the left as well as the right in the effort to drive democracy back into the hole where it belongs. Bush and Kerry can run because they’re funded by basically the same concentrations of private power. Both candidates understand that the election is supposed to stay away from issues. They are creatures of the public relations industry, which keeps the public out of the election process. The concentration is on what they call a candidate’s “qualities,” not policies. Is he a leader? A nice guy? Voters end up endorsing an image, not a platform.4

If a sacred American institution, such as democracy, can be transformed into a tool of capital yet maintain almost unanimous support as egalitarian, so too can the criteria of justice and equity obfuscate more problematic inner machinations in urbanism and urbanization. This is not to say justice, equity, and participatory processes should not be explicitly pursued, but there should also be recognized that the use of such methods can also be a means to an end, a language, and a framing that can function as a justification for or obfuscation of the status quo.

The opportunity for an equity-based form of urbanism and justice must also exist beyond the confines and mechanisms associated with American democratic practices. While it may be overly critical and nihilistic to propose that an insistence on democratic values permits the power of capital to remain unfettered, it is also a reality of the relationship between consumerism and governance in contemporary America. While the infamous legacy associated with American urban renewal programs has left an indelible mark on both the American psyche and the role of the designer/planner in the wave to develop counter methods that operate in opposition to the modernist design imposition, the pendulum has swung so far, and the design imposition so demonized, that designers must instead find ways of manipulating so-called democratic processes to legitimize the intuitive impulse to action.

Design is an inherently optimistic pursuit. To endure the pain of the design process, which is typified by the perpetual trampling of ideas beyond recognizable form, one must constantly be self-assured that each step has something which can be salvaged. Regardless of how seemingly insignificant that salvaged element or idea may be there has to be a belief that it can be designed to be a little bit better than if left alone. Is it not an inherently just act to attempt to achieve an ideal against all odds? If not justice, does it not reflect an inherent potentiality or intent to be? What is the justice associated with beauty? Is it not important for humans to experience the sublime or be filled with wonderment? To take away the aesthetic experience from life would be truly unjust, and thus, is the provision of an aesthetic dimension of life and space not a form of justice? A beautiful building, a romantic tree-lined street, a unique sculpture in a plaza, or a touching memorial, are these acts of creation not fundamentally some tiny form of justice? While it may be over the top to attempt to state that all design is inherently just, by contrast, to assume that justice and equity must be explicitly the intention for design for it to be just is reductionist and inherently devalues the potential of design.

What is concurrently devalued is the role of intuition. The need for things to be explicit is the material of capital flows, the power of the implied is the poetics of art and the foundation of culture. The urban landscape, as a realm for design in America, has been consumed by the need for the explicit. Trees cannot be discussed for their beauty; they cannot be discussed for their ephemeral qualities through the seasons, such as the smell of blossom in the spring or the crisp aroma of light decay of leaves fallen to the ground in fall. Trees are instead monetarily measured for their ecological benefits, validated through their ability to draw down carbon, increase property values, or how they can create more equitable neighborhoods. While the explicit value of land as a commodity is well understood in America, the implicit value of the constructed landscape is not. This is prevalent in the ubiquitous treatment of sidewalks as a drab and un-designed territory left to entropy. Where there is little implicit understanding of constructed landscapes as a realm for poetic expression, there is little hope for the beauty of the constructed realm to be understood as just. America will, unfortunately, continue to perpetuate its abject ugliness. The realities of this realm have so affected the imagination of its possibilities that American expectations for what it could and should be are limited.

Sidewalks are unassuming, standardized pieces of gray concrete that are placed between roadways and buildings, and their common appearance belies their significance and history as unique but integral parts of the street and urban life.5

The American sidewalk is likely one of the most physically nondescript and uninteresting sidewalks in the world, and, while possibly an accurate reflection of the American perception of the public realm, the gray nondescript nature of most American sidewalks cannot be understood to reflect the values of other cultures, only that of America. If sidewalks can be understood as reflections of cultural values, then through examining sidewalks and associated urban landscapes of other cultures, insight can be obtained concerning the differences in how the broader public realm is perceived.

Sidewalks, as is the case with landscape, are plagued by the problem of invisibility. They are so omni-present, and their condition so ubiquitously disregarded that the general public, politicians, and even architects don’t see them as places where aesthetics has critical value. While they are physically present, they are also invisible. This invisibility is in large part due to the car. As Sennett notes, “the erasure of alive public space contains an even more perverse idea-that of making space contingent upon motion.6 Culture produces forms of invisibility unique to that culture. This is to say that being thoroughly steeped in one’s own cultural milieu while potentially providing deep insight as a ‘citizen expert’ also produces equally impressive blind spots. The reality of the American sidewalk as an invisible, perpetually disintegrating realm, barely maintained to a subsistence level suitable for traffic, is not unrelated to another form of collective blindness in America, which is that the United States refuses to see itself as anything other than a democracy.

…the US has essentially one political party, the business party, with two factions called Republicans and Democrats. And they consistently follow policies that are in the interest of their business constituency and sometimes of some help to the population, sometimes not.7

The myth of America as a democracy allows for the perpetuation of a system that is not. In 2014 a study undertaken by Princeton University and Northwestern University, published by Cambridge University online press, concluded that America functions not like a Democracy but instead an Oligarchy.8 The problems and invisibilities of the American sidewalk are thus not inherently a result of mismanaged resources resulting from a democratic process, but instead a neglect that originates from a system of governance which citizens do not direct but instead is directed by capital.

An Oligarchy is a power structure in which power rests with a small number of people. These people may or may not be distinguished by one or several characteristics, such as nobility, fame, wealth, education, or corporate, religious, political, or military control.9 In the United States the top 1% own a greater share of the wealth than the entire middle class which in 2021 amounted to 27% of the total wealth of the country.10 Technically legal yet utterly immoral forms of government corruption by capital via lobbying and campaign contributions, compounded by the use of the electoral college for presidential elections which does not reflect the will of the general population, creates a condition in which capitalists have a controlling grasp over American government. Not only does capital hold disproportional sway in the American system, but corporate consumer-based tactics have also corrupted the practitioning of democracy. As noted in a 2002 interview, Dick Morris, President Clinton’s policy and campaign strategist for the 1996 election, said, “I felt the most important thing for him [President Clinton] to do was to bring to the political system the same consumer rules philosophy that the business community has. Because I think politics needs to be as responsive to the whims and desires of the marketplace as business is.11

Unfortunately, participation in the ‘democratic’ system in the United States is merely a palliative that affords the participants the belief that they have power and that their rights are affirmed. Participatory systems and exercises emulated on and derived from American democratic principles do not inherently provide agency to address underlying issues and often only provide the illusion of choice for determining band-aid solutions that treat symptoms, not root causes. “Although we feel we are free, in reality we like the politicians, we have become the slaves of our own desires.”12 The discourse of participation in design upholds the myth of American democracy and perpetuates a form of exceptionalism that reinforces a relationship in which global capital is not beholden to civil society or national sovereignty.

While the construction of individualism through the formation of identities resonates with the lived experience, it also has roots in ancient western philosophical thought. In American discourse, the importance of the individual as expressed through identity is intentionally elevated, not primarily by a civic-oriented desire to create a more egalitarian or just system, but as a way to encourage the self to be defined through commerce. While it is possible, as an individual, to resist this claim and live one’s life per an individuality not entirely defined through capitalism, such a lifestyle would, in most cases, represent an understanding of the American system uncommon for the general population. In most cases, the mainstream collective cry of those who fight and advocate for the recognition of individualized identities do not comprehend the degree to which such advocacy ultimately reinforces marginalization and subjugation via corporate interests. Within the American context, the attempt to achieve greater recognition of differentiated identities has the intended yet a widely imperceptible result of utilizing the discourse of identity as a driver for consumerism.

Being ‘heard’ in the form of participatory governance is the satiating of a desire cultivated primarily through America’s unique form of laissez faire capitalism. To borrow a phrase from Diane Davis, it is merely “rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic,” and to further the analogy, the intense focus and creating an equitable arrangement of deck chairs means that no one is focusing on who is stepping into the lifeboats and lowering themselves to safety. Lamenting the state of American politics, Robert Reich, a member of Clinton’s Cabinet from 1993-1997 said: “It suggests that democracy is nothing more and should be nothing more than pandering to these unthought about very primitive desires. Primitive in the sense that they are not even necessarily conscious, just what people want in terms of satisfying themselves.”13 If American democracy no longer is predicated on establishing a collective, social, and civil realm resulting from advantageous economic conditions for an elite ruling class produced through a hyper-individualized general public, the American discourse by and about the public is dubious at best. While such a framing of the American condition is worrying for the state of the nation and its people, it becomes highly problematic when framed as an exemplar, arbiter of world order, and nexus of global capital flows.

The industrial world had mostly been destroyed by the Second World War. The US, which was already the richest country in the world, almost quadrupled industrial production. I mean, we literally had half of the wealth of the world at the end of the Second World War. US manufacturers had an enormous surplus and they needed a market. Well, where’s the market gonna be? Only in the other industrial societies. So they had a real stake in using taxpayer funding to help the other industrial societies reconstruct and be not only a market for US industry but also an area for expansion. That’s how multinational corporations really got started.14

While the deconstruction of the relationship of capitalism to American government is undoubtedly a topic suited for a lifetime of research, the key with regard to the definition of the public realm and urban landscape is that it is not inconsequential that a discourse so focused on participation exists and produces such a dysfunctional, ugly, and disinvested public realm. This is not a causal relationship. It is not to say that participatory processes and governance inherently produce terrible urban conditions, but what it does suggest is that the focus on participation and ‘democratic’ values is not only a self-fulfilling cycle but draws attention away from the addressing the issues by invoking the democratic myth, which inherently perpetuates gargantuan blind spots in the progressive liberal outlook.

Constructed America is an ugly territory, and some would argue the ugliest in the world. The American public realm will always be ugly because of the nature of the American public as hyper-individualized consumers catered to by corporate interests, which inevitably results in common spaces as grounds for contestation. The urban landscape is conceptualized as a realm of negotiation which does not engender its own identity but is only the amalgamation of contesting identities. The public realm is not viewed as a place where culture exists; it is only viewed as a political realm in which people fight for recognition of their identities. If the landscape is only political and is not viewed as a place of culture, as a place of beauty, as a place intended to have its own identity, it will never be seen as a place for aesthetics. If the urban landscape can only be understood through its political dimension, then there is little room for it to be understood as anything but contested grounds, and therefore can only be an ugly territory. Where there is a lack of beauty and propensity for neglect, fear also exists.

Fear pervades urban life and public spaces. Sidewalks, like other public spaces, entail the possibility of danger and even violence. They can be disorderly and expose people to uncomfortable encounters. For this reason, cities and urban residents have attempted to minimize disorder by legislating certain uses and users away from public sidewalks.15

Nevertheless, while the American exceptionalist outlook presupposes the conditions associated with sidewalks, and by extension, the urban landscape, to be universal, the truth is that not all places have the same approach to their public realm. China poses an interesting contrasting condition where the definitions of self, identity, public, and the relationship to governance and capital are very different, where the sidewalk poses a compelling entry point. The aesthetic component is immediately visible when experiencing or examining the Chinese sidewalk. While the existence of objects, obstacles, steps, bollards, poles, wires, and structures is both more prevalent and haphazard, underpinning what at first appears to be chaos is an aesthetic impulse that establishes the urban landscape as a place for design, aesthetics, and consideration, it is the opposite of a gray nondescript unimaginative territory.

As noted, the aesthetic of the American sidewalk is primarily defined by its materiality. An engineered cementitious mixture that creates large uniform slabs prone to breakages and cracks provides a vast dullness and emphatically expresses its deterioration. The Chinese sidewalk, by contrast, is rarely a poured material but typically comprised of units of stone, brick, or concrete. Units are well suited to Chinese industrial processes; they can be fabricated, shipped to the site, and rapidly deployed by a large labor force. At every step of the process, there exists a kind of vernacular aestheticization. Units are not designed simply for slip resistance; flowers, patterns, or colors are imprinted or cut. When being laid on the site, patterns are often created, zig zags, checkers, lines, and interlocking patterns are common among the cheapest and most common of spaces and applications. In fact, an almost inverse relationship occurs in the poorest and least developed regions which tend towards the more unique and flamboyant paving patterns. Even through a superficial and cursory examination of sidewalk materiality, we can ascertain that China and America not only have completely different public realms but also have entirely different outlooks concerning the role design plays in the urban landscape.

A mindful examination of the Chinese public realm is necessary to establish new concepts and frameworks for defining the public realm and urban landscape. Viewing the Chinese condition through the lens of American discourse is only inherently problematic, as it narrows the potential for new forms of knowledge while denying legitimacy to cultural systems and opposing systems of governance based on their unfamiliarity; it is also unjust.

WAR AND THE MAKING OF INVISIBLE LANDSCAPES

The invisibility of the profession of landscape is one of the overarching and deep-seated issues in the discourse of landscape architecture. Even the founder of the profession, Fredrick Law Olmsted, lamented the lack of recognition and understanding of what designing the landscape is.

“If people generally get to understand that our contribution to the undertaking is that of the planning of the scheme, rather than the disposition of the flower beds and other matters of gardening decoration, it will be a great lift to the profession.”16

Architecture, at its core, is constructed and as such, has an intrinsic clarity. It may not be hyperbole to state that it is impossible to imagine any example of architecture that is not constructed. By contrast, the discourse of Landscape Architecture often attempts to contest its constructed nature and is, therefore, less intrinsically clear and more conflicted than architecture. Landscape Architecture is eternally bound by its engrained conflict, cyclically confronting, embracing, then subsequently rejecting its own constructedness. The nuances of landscape’s intrinsic nature-culture dialectic formulate an innately more philosophical discourse, although the architectural community would widely contest such a statement.

The perception of Landscape Architecture as predominantly nature-based, as opposed to a culture-based field, ultimately leads to differing definitions of what and where the landscape’s physical, conceptual, and academic territory resides. Culturally contingent understandings of where landscape resides produce culturally specific ‘blind spots’ or invisibilities in the landscape. American is deeply ambivalent about the idea of nature as constructed; however, not all cultures are similarly ambivalent.

The Chinese culture has long since sidestepped this issue in the long-held belief that nature itself can be enhanced by correctly constructing landscapes and architecture. This understanding is the foundational ethos of the practice of Feng Shui, which entails the beneficial management of qi flows. “Qi is usually translated as “vital life force,” and according to Classical Chinese Philosophy, qi is the force that makes up and binds together all things in the universe.”17 The qi of a river, mountain, site, or garden can be enhanced through design and physical manipulation. The Chinese idea of nature is not necessarily a wilderness but instead understood to be that which can be constructed and manipulated to be ‘better’ than nature could be on its own accord. This results in a condition in which there exists no inherent conflict in the idea of a constructed nature. This concept of nature manifests not only as an entirely different outlook of the built environment but also in utterly different practices of Landscape Architecture and Architecture. A fundamentally different understanding of the relationship between constructed and non-constructed environments comes with its own unique blind spots and invisibilities.

While the American urban discourse invites conflict and reframes it as necessary or unavoidable, by in large, violent political conflict in American streets is relatively nonexistent. While America does have a history of protest and, in some cases, rioting, the prospect of all-out war has historically been minimal. The civil war was the last war to be fought on American mainland soil. Additionally, it could be argued that any armed conflict representing a true threat to American sovereignty, other than self-inflicted, would date back to the war of 1812 and the preceding Revolutionary War. While the American desire to go to war abroad has remained unsatiated since WW2, the concept of all-out war and occupation of America, perpetrated by foreign nation-states, is extremely remote. While during the cold war, McNamara’s strategy of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) elevated fears and the distinct possibility of nuclear annihilation. However, barring the adornment of some suburban homes with bomb shelters, all aspects of American life and livelihood, including urban planning, real estate development, and design, professions charged with designing and creating the urban realm seemed to progress, unshaped by the possibility of war.

The Chinese relationship with war is very different. While America repeatedly ‘finds’ itself abroad at war, since the establishment of the Peoples Republic of China (PRC) in 1949 China has only on a few occasions sent soldiers over the border and, in general, is lauded by the international community for becoming a world superpower without the use of overt force and violence. While contemporary China is virtually war-free, China’s early modern history has formulated a unique psychological relationship to war, which is not only profoundly internalized but manifests in China’s urbanization and built form.

In the one hundred years predating the establishment of the PRC, China was in a state of almost constant and perpetual war. European colonial powers forcibly opened port cities for trade. Rebellion against the Qing dynasty sparked the largest civil war in the history of the world, with 20 million casualties spanning two decades. Repeated wars with the Empire of Japan, including WW1 and WW2, resulted in a significant loss of territory. Revolution precipitated the fall of dynastic rule, then further descended into a fragmented ‘war lord’ decade. The resurgence of revolution and civil war between the Republic of China and the Chinese Communist Party was partially halted during WW2 and reignited upon the surrender of the Japanese, who raped, pillaged, plundered, and bombarded Chinese cities. The appendix to this article provides a more accurate timeline of these events. What is essential to recognize is the roughly one hundred years of effectively continuous warfare and conflict which characterized China before the establishment of the PRC. During this tumultuous period in which a modern nation-state was forged, there existed a growing concern for how to protect civilians and the general public during times of war, with particular attention paid to the bombardments endured during WW2.

In 1951 two years after the Chinese Communist Party established the Peoples Republic of China, the first edition of national building codes was issued. In the first edition of the national building code, there was a section on Civil Air Defense. Through subsequent editions of the Chinese national building code, the specificity and regulations associated with war-proofing buildings were not only further engrained into the building code but were expanded in scope, application, and variety. The ubiquity and uniformity of the national building code designed for public safety in the event of war produce unquestionable and physically present invisibilities in the Chinese built environment, public realm, and urban landscape. One of the more intriguing invisibilities in the Chinese urban landscape is the persistence of structures, spaces, and boundaries associated with Civil Air Defense policies aimed at protecting civilian populations from bombardment during times of war.

Physical manifestations of wartime mentality are not only seen in the large-scale known and rumored infrastructural projects and spaces. For example, Beijing’s main street ChangAn Jie is suspiciously long, straight, and wide, with ample architectural setbacks providing enough space to land large airplanes or host many tanks abreast. Vast, secretive underground networks of tunnels intermingling and intentionally obfuscated by expansive public transport metro networks are some of the more obvious examples of how the anticipation of war shapes the Chinese Urban landscape. Architectural manifestations of war anticipation run so deeply that they have become invisible. These architectural manifestations exist not only as the urban form itself, in the design and organization of the streets and metro, but also in the Chinese homes that have come to define China’s unique form of urbanization.

Ask almost any person living in China, most of whom now live in high-rise buildings, if they know what the giant submarine-like doors in the parking garage of their tower are for. Inevitably one will receive a blank stare or possibly even the query, ‘what doors?’ Maybe it is the lack of an architecturally trained eye; maybe it is the lack of inquisitiveness resulting from the culturally specific aversion to questioning order; however, it is more likely a form of culturally conditioned blindness. Whatever the answer is, the giant hulking mass of concrete-filled steel blast doors as the main entry feature to everyone’s home is typically not recognized, let alone its origins understood.

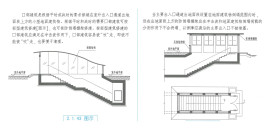

According to the Chinese national building code section ‘Code for design of civil air defense works of dual-utilization of peacetime and wartime,’ (平战结合人民防空工程设计规范) all subterranean parking levels of all buildings are to be designed as bomb shelters. Among experts in Chinese building code, it is generally believed that for standard forms of bombardment, the parking-garage-bomb-shelter is sufficient, however, there is less general consensus and confidence with regards to nuclear attack, yet given the ubiquity of the code, considering every building built in China since 1951, taken together there does exist a substantial wartime infrastructural security network.

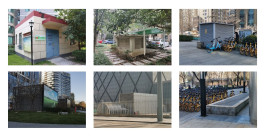

A parking-garage-bomb-shelter then produces an intriguing series of externalities that must be considered. If people are trapped, how will they get out? Or conversely, if people must stay below ground for prolonged periods, how will resources for sustaining long-term subterranean life be supplied? These externalities in the form of architectural cores are prescribed through building codes and leave an indelible mark on the urban landscape. Civil Air Defense cores are highly regulated with a variety of different functional types. For example, some cores are designed so hoists can be attached to lower resources or hoist up people. Some cores have inbuilt ramps with easily removable or blast-away coverings to allow cars and trucks to go in and out in times of emergency. Complex organizations of drains, vents, ramps, stairs, hallways, and blast doors are arranged to create an easily accessible, highly secured subterranean realm designed for sustained long-term use if needed.

While the basics of the functionalities are widely understood, the logic is often not pushed to conclusion. It is true that even the idea of discussing the functions of Civil Air Defense cores and attempting to better understand them in hopes of designing less intrusive outcomes becomes uncomfortable as the gruesome and destitute conclusion of pushing the logic further emerges. Although it is not possible to walk 200 meters in the newly constructed regions of a Chinese city without coming across at least two or three Civil Air Defense Cores, they go unnoticed, and this type of invisibility is problematic for those charged with designing the realm of the Urban Landscape.

The Civil Air Defense Cores not only pose complex design problems and typically produce unsightly carbuncles throughout the city; they also serve as an example of how designing the landscape is inconsistent from culture to culture. The entire Chinese city is essentially built as a giant bomb shelter, and this invisible reality reflects onto the urban landscape, although it is mostly not seen. America has no conceptual or physical counterpart. The idea that the prospect of imminent war could utterly define every street, sidewalk, and home in America built since WW2 is an idea so far removed from the American psyche and reality of the built environment that there exists very little common ground for understanding this dimension of the Chinese public realm. It would be an oversimplification to state that the Chinese urban landscape is fundamentally or only defined through the mechanism of a wartime mentality. However, what is interesting is how invisible, seemingly apparent realities can be. It is interesting to consider how our own cultures can obfuscate our abilities to understand our own constructed conditions and, therefore ourselves.

Through comparative analysis, it becomes clear that different cultural and social constructs create different forms of invisibility and, therefore, different kinds of public and private realms. It should be noted that in a civilization as old as China in such a vast territory, had the decades of modern war and revolution played out differently; the region could easily be a handful of different countries, each with a related yet ultimately unique culture. Chinese cultures, regions, geographies, and ecosystems are so diverse that the political understanding of China as a monolith is purely that, a political construct aimed at unifying otherwise highly diverse cultures and territories. On the contrary, given the long dynastic history, a continual ambition exists to unify a grand territory into a monolith that has persisted for millennia. As is true with everything in China, it is both, and it can be understood as a monolith and or a collection of highly distinct regions, yet even with this potential for ambiguity between monolith and fragmented collective, there still persists a clear if not contested understanding of what is or is not China and therefore what is or is not Chinese culture.

By contrast, the boundaries of American culture are more ambiguous. This ambiguity is also a point of contestation. In the United States, culture is imported, exported, and hybridized; topics such as the origins of Jazz music and continued argument over cultural appropriation are only possible in a cultural milieu that is defined through its flux. This cultural flux, by some, is understood as lacking inherent culture, while others argue that the navigation of cultural flux is the American cultural identity. Regardless of where one falls on whether America has a culture or not, discernable cultural boundaries of where one cultural system starts and the other begins cannot be perceived nor identified with any accuracy. While there are benefits associated with not being confined to any one specific cultural system, there exist a problem which reverberates through to the national psychology and, therefore academic discourse. Due to the amorphous and blurry boundaries of American culture one is inevitably confronted with a choice about which aspect of a culture to identify with; therefore, culture becomes an aspect of identity through choices. Culture, as experienced through individual choice, is fundamentally different from a culture that is less ambiguous and not a matter of choice.

Not unlike the invisibility of wartime mentality in the Chinese urban form, the idea of culture and identity as a function of choice, free will, and democratic values represent a territory laden with invisibilities. The western liberal discourse on identity exhibits stubborn contradiction, which claims to be globally aware and culturally sensitive, yet given its formation in an ambiguous multicultural framework, it, therefore, becomes difficult for the American psyche to truly internalize the understanding of culture as anything other than one’s own personal choices. The focus on personal identity is so entrenched that one’s identity is in fact considered to be the ‘intersection’ of many identities in which the self is placed at the center, as the identity of the individual myopically consumes American discourse. One’s culture, one’s family, one’s nation, and one’s own body is seen as a series of individual identities which together create another identity. American psychology is, therefore, entirely consumed by the self and the ego. The idea that one chooses their culture inherently reinforces the ego. This logic makes it difficult to empathize with a cultural system in which there is no such thing as an individual or a culture in which the individual is ideally without ego.

The difference between western and eastern cultures at its philosophical root is the degree to which the ego plays in relationship to society. While this may be something that can be cross-culturally perceived, it is not easily internalized. Many Chinese social constructs, such as ‘face,’ can have no cultural equivalent when being compared with a culture where the self centers the perception of society and the world.

Face operates with reference to a conglomerate of institutions and value that might be characterized as communitarian: it involves the loyalty associated with kinship, the reciprocity that makes good neighbors, and the embedded, stable social relations that are typically thought to characterize the rural context… In Mayfair Yang’s analysis, for example, the centrality of face is intimately tied to the Chinese “relational construction of personhood” in which “threats to one’s face constitute threats to one’s identity, which is constructed relationally by internalizing the judgement of others in oneself” (1994:196) Thus, face is credited as one of the bases, if not the basis, for articulating the distinctive conception of the person that governs the individual’s relation to society in China (see, e.g., Liang 1949; Fei 1992: and Hsu 1967).18

To lose face in Chinese culture is one of the most embarrassing things to have happen to a person. Losing face is usually not a personal act but a communal one; there is often a person who makes another lose face in front of others. Making someone else lose face also carries with it a stigma. When face is lost, it is relational; both the person losing face and the person who makes another lose face and the audience are stigmatized. Losing face to an audience of peers or, even worse subjugates is the highest form of insult. Coming from a western background, this notion is hard to grasp. Over time it is possible to gain an understanding of how face operates in a social context; however for any non-Chinese, the emotional impact is never truly felt, it is possible to sympathize, but empathy is not entirely possible.

Face refers to one’s social status in the eyes of others, which can be accumulated, lost, or given to another and is said to be a key guiding relations between Chinese people, rural or urban.19

Concerning the problematic aspects of face and how it functions in business settings, its result is a condition where people in positions of power should never be corrected in situations where they are incorrect or wrong. Even when a boss is making an objectively false statement or requires a project schedule which is not possible, questioning or correcting someone in a position of power risks them losing face. In western culture, when designing a project, one operates on the premise that transparency about a project schedule or potential setbacks is critical in allowing other consultants, designers, or managers to react and adjust accordingly. This is not the case in China. When the boss says they want the project open by a specific date, that boss will never hear anyone speaking up to say that this may not be a realistic request. It may be addressed privately or in a more social setting, such as a dinner. However, it would not typically occur in a formal or official capacity in which ‘ideally’ no one speaks up for fear of making someone else lose face, which, in turn, would also reflect poorly on everyone present.

It is more cultural faux pas to announce that the project will not meet the schedule than to simply allow it to miss its intended deadline. Face is so central to the construction of identity that to make someone lose face is a personal assault; therefore, it can be very dangerous if someone in power loses face because the audience is also, to some degree, responsible.

Having participated in a landscape project for a developer which was located at the center of one of the most popular districts in Beijing called Sanlitun, the complexity of the relational construct of face played out in an unfortunately predictable way. Sanlitun is one of the major entertainment districts of Beijing and could be considered an ‘inverse’ of the American Chinatown. Chinatowns across the western world are havens for Chinese culture in foreign lands, the inverse in Beijing is Sanlitun, a western haven set within the heart of the capital city of China. At the center of Sanlitun is a shopping and entertainment center called TaiKooLi. Across the street from Taikooli, the ‘lifestyle’ mecca of Beijing, the project for which we had been asked to design the landscape.

The building, designed by HOK, sits on a corner parcel of land, which has a slenderness very uncommon in Beijing. Beijing typically has very large, almost always square plots of land. The slender site created a condition in which the landscape for the project could not be internally focused, as is common in Beijing. However, instead, the design problem had to be focused on creating a functioning sidewalk. For foreign architects operating in China, such as HOK, it is required to have the Local Design Institute (LDI) draw and stamp the construction drawings. To save cost, the LDI will design the basement levels to ensure adherence to all the architectural codes, including the extremely stringent Civil Air Defense codes.

Additionally, it is not uncommon to have the Local Design Institute design the basement levels and parking while the foreign architect designs everything above ground. This in part, is viewed as a way to save cost but, more importantly, is because it is possible to get construction approval for the foundations and basement levels before the design of the upper levels is completed. This inevitably creates a coordination nightmare, and the landscape is always the most affected by poorly coordinated and badly designed buildings. This project suffered from such a mismanaged coordination issue in the most embarrassing way. A giant Civil Air Defense core protruded from subterranean portions of the building directly at the mall’s front door. Both the design architect (HOK) and the local architect (LDI) had not noticed that a Civil Air Defense core was to be constructed in such a location as to block the project’s front door.

That which is typically invisible became a glaring and unavoidable problem. The core constructed directly in front of the key entrance to the project was the physical manifestation of face lost. Quite literally, the ‘face’ of the building, as personified by the front door, was lost, no longer visible from the sidewalk. Two years prior, we had informed the client of this impending disaster when joining the project. However, given the embarrassment of addressing such a concern with the distinct possibility of causing a superior to lose face in conjunction with the perceived lower status of the Landscape Architect compared to the building designer, the issue was never elevated.

The existence of the core in front of the door remained unaddressed until it was constructed. Tensions began to run high when the core became visibly present during the construction process. The lower-level boss who had been in charge of managing the design was removed from the project or at least was never again in attendance during meetings. However, the ultimate realization of the core’s existence and its inability to be relocated, coupled with the documented proof that the project team had not elevated the issue two years prior, resulted in the big boss’s volatile emotional state having lost face so publicly. Both the boss’s face and the face of the building had been lost. Many new design alternatives were examined, yet none could do anything to fundamentally address the problem, which was that the face of the building had been lost. No solution would fundamentally alter this reality.

The process continued to degenerate to the point where the landscape designer’s role became to merely translate the big boss’s sketches into a constructible design. In a meeting that, at the time, we were not aware would out last, the big boss informed us and his management team that we had not followed his directions. We informed him that the design was directly based on his sketch. He denied having made any sketch. When the photo documentation of the big boss drawing his scheme on the whiteboard during the prior meeting was projected onto the screen in the meeting room, the big boss lost face yet again, and this time in front of his subordinates, and it ended up being the last meeting we were involved in on the project.

The social construct of face creates and entirely different construct of the public realm. What does it mean when a building loses face? What does it really mean when such an externality, like a gate, a door, or a core, can drastically influence or create one’s personal identity as constructed in relation to the general public? What is the relational construct of face to the public realm? How does the social construct of ‘face’ differently construct urban form? If the façade of a building or the quality of the landscape can play an integral role not just in public and shared identities but the actual construction of individual identities, what does that mean for the design of urban landscapes? The cultural construct of Face ”function[s] against the backdrop of “public opinion,” the known or knowable-able consensus of “society” as to the standards of correct conduct.20 By extension, the quality, and design of the urban landscape plays a role in ‘giving face’ to those who exist and interact within it. Thus, designing in the Chinese urban landscape transcends social, financial, or ecological metrics, as the relationship to ‘urban face’ contains a dynamic that can construct or destroy the relational contract between self and community. The idea that a unique and specific social relation, face, which also plays a critical role in identity in relation to others, is yet another component that defines a public realm, unlike its western counterparts.

At almost every turn, we begin to see a drastically different construct of China’s landscape and public realm. While it is simple to perceive the streets and sidewalks of the Chinese city, which technically function identically to their American counterpart, the public realm they create could not be more different. It is not dissimilar to how the West, in particular, America, views the monotony of Chinese housing. Unfamiliar scholars, academics, and aesthetic thinkers point to the Chinese form of housing and immediately associate it with the woes of Pruitt Igoe, and perceive that China is following in the footsteps of America and therefore making the same mistakes. The American psyche is so deeply scared by racism, discrimination, ghettoization, and urban renewal programs that the spatial and formal similarities of Chinese housing to the American low-income housing projects will automatically create negative associations within the western mind. However, the Chinese cosmological structure, qi, ideally orients the home facing south, with mountains to the back on the north and water to the south. This southern-facing orientation typifies the ideal traditional home orientation. These traditional values in combination with the Chinese national building code, which requires a specific number of hours per day of direct southern daylight exposure in conjunction with the modern history of worker housing typologies established as part of centrally planned industrialization, has resulted in a specific housing typology which in appearance may be identical to American low-income housing projects, but in cultural origin, architectural function, and market desirability, not remotely comparable. The same is true for the urban landscape and public realm. While the road and sidewalk may look the same, nothing could be farther from the truth. Moreover, like the woeful results of Pruitt Igoe, the American public realm is sadly vacuous of identity beyond that which can be constructed by politics, conflict, dispute, and ultimately neglect.

Thus far, this article has addressed very ‘concrete’ elements such as sidewalk pavement and Civil Air Defense Cores, which produce a very different public realm that cannot be evaluated according to the same logic as the American counterpart. This argument attempts to engage the relationship of the built to the social. However, what truly distinguishes the Chinese urban landscape and the associated definition of the public is predominantly defined through cultural enactment in the urban landscape. While the physical accounts of burdensome policy, heavy-handed planning, and mega infrastructure, to some, may induce a depressed reading of the Chinese public realm, by contrast, the cultural performativity in the urban landscape provides, by most accounts, a humor-filled, joyous, and ultimately unique precedent for the relationship of landscape to culture.

MYTHOLOGY IN THE CHINESE URBAN LANDSCAPE

Qingming Festival, also known as Tomb Sweeping Festival, is a fantastic time of year. It is a traditional Chinese festival celebrated on the first day of the fifth solar month, placing it in the early spring. The traditional Chinese calendar is a lunisolar calendar which means that it is formulated both through the movement of the sun, similar to the Gregorian calendar, as well as the moon, which through its cycles, creates a highly differentiated annual calendar in which many holidays and festivals occur in different periods of the year. The moon dictates many important days in the traditional and contemporary Chinese calendar. The interplay between lunar and solar cycles creates a vibrant and more exciting year, which does not fall prey to the monotony of an annual calendar pegged only to the sun. The moon’s schedule, in contrast to the sun, seems to play to its own beat; it is dynamic, changing, unexpected and surprising; a culture that attends to the cycles of the moon undoubtedly contains poetics that the sun does not afford.

While the sun controls the daylight and provides warmth, the moon controls the fluids of all bodies on earth, from the oceans to our cerebral fluids. Over millennia the agrarian civilization which came to define China was very much in tune with the relationship of the moon to the cycles of agriculture. Major lunar dates in the Chinese calendar are inseparable from festivals which typically coincide with major agricultural events such as harvest in the fall and sewing seeds in the spring. While it may seem divergent or extraneous to recount holidays, festivals, and their lunisolar origins when contemplating the public realm, it is precisely these types of characteristics that should be considered in reframing the western lens to produce a reading of the Chinese public realm which is based more closely on the terms through which it is lived and experienced.

The question is, what does it really mean to have an urban landscape and cultural realm defined so heavily by the moon? The moon is not simply a means for telling time differently; the larger cycles of the moon, as defined through the Chinese zodiac, is also a means for structuring and predicting personal characteristics, fortune, luck, and identity. Not only does the moon play a role in one’s own given personal identity from birth, but it also has ramifications for the nation. For example, Dragon and Tiger years are more competitive in academics as more couples prefer to have children in those years. The moon structures Chinese society in ways that no corollary exists in the west. As such, the moon certainly plays a role in structuring the Chinese urban landscape. There appears to be little scholarly work concerning how one’s outlook and perspective on the urban environment changes when the timing of key societal and cultural events are not only linked to national and political bodies but also, or primarily, linked to celestial bodies and their cosmic relationships.

The year according to the moon, is never dull. The moon both creates a more intricate short-term engagement as holidays, festivals, and critical annual markings seem to jump around year to year, never landing on the same day of the Gregorian calendar. Yet the moon, through the Chinese Zodiac cycle, also creates a much larger awareness and context for the passage of time. Breaking one’s life into what is inevitably only a handful of Zodiac cycles gives pause for reflection and contemplation. Passing a twelve-year cycle of the zodiac somehow carries with it not only a gravitas unequaled by marking time in decades but carries with it a cycle of scale more significant than the cycle of a year, which is marked by the circumambulation of the sun. Through the Chinese lunar calendar, a different perception of time and cycles can be understood, one that is both more active and present in the short term yet also broad, expansive, and understood to predate and extend past one’s lifetime. A society so influenced by the moon will create a wholly different kind of urban and public realm.

Although it is not a lunar holiday, the Tomb Sweeping festival does have a relatively unique relationship to the contemporary urban landscape, in particular, streets and sidewalks. As is the case with many Chinese festivals, while the dates maybe officially set in the calendar, those dates represent more a crescendo of activity in which the timing and frequency of associated traditional enactments often depend on the gravitas of the festival, such is the case with Tomb Sweeping. While traditionally, families are supposed to go to the graves of their ancestors and clean or ‘sweep’ their tombs, as well as provide food and drink for offering, most people with little knowledge of the location or access to the burials of their ancestors enact the offering in the street through the burning of paper articles, primarily faux money, although burning paper cars, paper houses, and paper suits are also not uncommon. These articles are burned so that the ancestor may have some money, clothes, and stylish transport in the afterlife. It is also not uncommon for the holiday duration to burn at least once a day to ensure enough assets are provided for the year to come. While burning does occur throughout the year, as families mark specific death anniversaries of loved ones, most of the burning occurs during Tomb Sweeping.

In the spaces of the city, most people will typically utilize the sidewalks and street corners for their offerings. An incomplete circle called a Hua Guo (画郭) or “painted wall” is drawn onto the pavement; the opening in the partial circle is intended to face the direction of where the ancestral grave is located to ensure that the ancestors are able to collect the money and assets while keeping out any other unwanted or lonely ghosts. The offerings are placed inside the partial circle and burned. When more offerings are to be given, a new circle is drawn, and offerings placed inside are set afire. Walking the streets during tomb sweeping is a bit like walking through a city after a firebombing or a zombie apocalypse; every street corner and sidewalk across the entire city and, indeed, the nation are aflame.

In an interview when talking about the mythologies associated with the painted caves of Lascaux in France, Joseph Campbell was asked why he sometimes called the caves ‘temple caves’ in response, Campbell noted: “Temple with images, stained glass windows, cathedrals, are a landscape of the soul, you move into a world of spiritual images.”21 He then continues to discuss the purpose of ritual and ritual spaces, specifically in the context of the Roman Catholic church, as an enactment which is intended to move one out of their day to day, and by extension beyond the self.

There’s been a reduction, reduction, reduction, of ritual, even in the Roman catholic church by God! They’ve translated the mass out of the ritual language, into a language that has a lot of domestic associations. So that, every time now, that I read the Latin of the mass I get that pitch again, that it’s supposed to give, a language that throws you out of the field of your domesticity. The alter is turned so that priest’s back is to you, and with him you address yourself outward like that, now they’ve turned the altar around, looks like Julia Childs giving a demonstration, and its all homey and cozy… and they play guitar. Listen, they’ve forgotten what the function of a ritual is, its pitch you out, not to wrap you back in where you have been all the time.22

What is essential to consider is the reading and understanding of the contemporary Chinese public realm and urban landscape as the place for enacting not only cultural activities but mythological enactments. What kind of urban realm is created when ritual is not bound or contained within specific theological spaces but instead the spaces of the city, the streets, and the sidewalk? The experience and reading of the urban landscape and public realm are transformed through collective mythology in the contemporary public realm, which extends beyond its physicality. In these moments, the Chinese urban landscape expands beyond mere politics and, indeed, beyond space-time itself. This act and others like it throughout the year make evident that the public realm must be conceptualized on an entirely different basis for which a western-centric discourse of the public is unfamiliar.

To counter the statement above, one might point to the many examples of religious or mythological expression in urban contexts in the west, people carrying the cross on Via Dolorosa in Jerusalem, a public audience with the Pope in Rome, a day of the dead parade in Mexico City, or Mardi Gras in New Orleans are all examples of communal, cultural and mythological events which take place in and redefine the public realm. However, many of the Chinese festivals contain characteristics that elude western corollaries. For one, in China, there exists a puzzling relationship in which belief in mythological or cosmological structures and systems is not inherently religious. The combination of communism’s absolute rejection of religion with the persistence of traditional Chinese beliefs formulates a kind of atheist mythology. In this condition in which mythology can be delaminated from the religious, it allows myth to be graphed directly onto contemporary conditions. Given the quasi-atheist nature of contemporary China’s ancient mythologies, festivals can be wholeheartedly supported by all governmental, political, and commercial institutions, resulting in unparalleled penetration into all aspects of life. America’s newfound sensitivity to multiculturalism has resulted in the de-religioning, decolonializing, and renaming of holidays previously presumed to be communal and shared mythologies. Thus, national holidays in America must carry no mythological connotations. By contrast, Europe’s unabashedly combined church and state result in holidays and festivals, which can have an urban-mythological dimension but are not without specific religious associations. Here again, China provides an alternate model which does not fit comfortably with the binaries established by western society and logic.

What is potentially unique is that through the delamination of theology from mythology, myth is, therefore, able to adapt and take on new forms, in which it can take on a contemporary dimension beyond the enactment of old rituals in new spaces, but one in which there exists the room to develop a contemporary layering and significance of the mythology which the Judeo-Christian theological orders inherently resist.

With respect to ritual, it must be kept alive. And so much of our ritual is dead. It’s extremely interesting to read of the primitive elementary cultures, how the folk tales the myths they are transforming all the time in terms of the circumstances of those people. People move from an area where let’s say vegetation is the main support, out into the planes, most of our planes Indians in the period of the horse-riding Indians, had originally been of the Mississippian culture along the Mississippi in settled dwelling towns, and agriculturally based villages. And then they received the horse from the Spaniards and it make it possible to venture out into the planes and handle a great hunt of the buffalo and the mythology transforms from vegetation to buffalo and you can see the structure of the earlier vegetation mythologies under the mythology of the Dakota Indians, and Pawnee Indians, the Kiowa and so on.23

Tomb sweeping is only one of what seems to be an endless calendar of mythological events throughout the year. Each festival has its specific forms of enactment and performance, which occupies and define the public realm in different ways. It is important to internalize that these are not simply cultural events that occur in the urban landscape, such as a block party, a parade, or a church gathering; what is being framed is the interrelationship between culture and the landscape, not only how they inform each other, but how engrained on is in the other. The aesthetic mythological dimension of the Chinese culture in the urban landscape either exists above or pierces through the political. The mythical dimension of the public realm has persisted beyond unimaginable hardship and globally unparalleled rapid changes in urbanization.

LEISURE IN THE URBAN LANDSCAPE

The striking experience of the Chinese urban-mythic public realm is enhanced by the contrast provided by technologically advanced urban conditions. However not all forms of cultural expression in the urban landscape have roots that stretch back millennia. Many forms of cultural expression are new and arise from China’s unique modern history, the establishment of the People’s republic of China, and experimentation in constructing the socially focused centrally planned economy. It is not simply the enactment of culture through the mythological or spiritual, but also through the everyday and mundane found in leisure activities. Leisure, particularly as it pertains to outdoor activities in America, is highly ‘medicalized’, which means that biological health and western forms of medicine focus heavily on the ‘medical benefits’ of athletics. The use of public spaces, particularly parks, is seen through the lens of athletic health. In China, self-cultivation, medicine, and health contain a cosmological dimension that transcends beyond the notion of correctly functioning and upkeep of the body’s biological systems. The harnessing, moving, and permitting the flow of qi, the energy source which connects all things, exists not only in a daily exercise regime but also in a beautiful painting or the situating of a home. To a degree, the ritualized enactment of all forms of Chinese leisure at some, often subconscious or embedded level, considers a relationship to the cosmological and, therefore, mythic dimension.

When traveling through the Chinese city, one is immediately struck by a different sense of how communal space is utilized, perceived, maintained, and bounded. The ubiquitous presence of walled spaces defines the city. Even the parks are walled. It comes as no surprise that the Chinese character for country or kingdom guo (国) itself is bound by walls. The walled spaces and communities which define the Chinese urban form, which of course, has its roots in the courtyard house typology known as the si he yuan (四合院), is, in fact, more defined by and related to the communist work-unit called the danwei (单位).

The industrial strategies of the late 1950s, aimed at the creation of “cities of production,” resulted in the dominant territorial and functional role of publicly owned “work units” (gongzuo danwei or danwei). At the same time, a draconian control of rural-urban migration characterized the period between the end of the Great Leap Forward in the later 1950s and Mao Zedong’s death in 1976. With lack of alternative employment opportunities and mobility under control, urban residential spaces became characterized by the individual and family dependence on the work unit.24

The work-unit (danwei) was more than a mechanism for organizing communal labor. It is also a residential community and a regulatory and policing body. As such, the work-unit was central to people’s lives and instrumental in reinforcing communal ideals and mindset. “Neighborhoods and communities were subsequently placed under the work unit (danwei 单位) which had its own socio-spatial configurations and came to control every aspect of an individual’s life – there was no space outside the unit for leisure.”25 This description of the danwei as allowing for no space outside the work-unit for leisure must also be tempered by other realities which coincide with such an account. It is essential to consider that in communist theoretical ideals, leisure was an important component in creating a perfect society.

For Marx, as a result of the abolition of the division of labour, any person can become an all-round developed individual who will be able “to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticize after dinner.” This transformation toward all-round development, as stated by Marx, would be possible through cultivations in “free time.”26

While conceptually free time and the ability to choose one’s own use of such time was not incongruous with communist values, in practice, many fewer freedoms were afforded. This is to say that there was an inherent understanding of the value of leisure time even if it was heavily controlled and regulated.

From the perspective of the CCP, successful leisure activities should follow three principles. The first and most fundamental principle was that people should join voluntarily. Official guidelines on leisure activities repeatedly stressed that these activities must match the real interests and hobbies of young people so that they would take part voluntarily.27

Beyond the recognition that leisure, although collectivized, was a critical aspect of an ideal socialist society, it was also viewed as crucial to national identity. China’s tumultuous period of modernization, constant war, and repeated violations of sovereignty earned China the title; “Sick man of Asia,” a derogatory labeling which has to this day propelled China to reclaim its once honored place not just center of the world, but of the cosmos. “Early socialist public health initiatives under Mao thus promoted healthy subjects as the wealth of the nation.”28 To consider leisure as something which was entirely disallowed in the pre-reform years, prior to 1978, of the People’s Republic of China does not provide a fullness of the complexity in the formation of contemporary manifestations of leisure in the Chinese public realm. A more mindful interpretation would be that leisure time was engrained as communal time and that the two, community and leisure, were inextricable. Ideals that today continue to shape the public realm and the urban landscape.

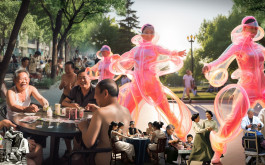

The contemporary Chinese urban landscape is a flood of energy unlike many places in the world; it is both highly machinic and fluid.

In the Chinese urban landscape, unique forms of leisure exist, creating a public realm with very few equivalents in the world. Cities in the ‘developed’ world of the global north predominantly define the physical public domain through the mechanisms of motion and transport; this too is true in China, yet there also exists a delirium of organic flows of dogs, people, street vendors, bicycles, tricycles, scooters, wheelchairs, of all shapes sizes dancing together like a school of fish and somehow, seeming impossibly so, seldom collide. The streets, parks, plazas, and medians are also filled with a different kind of wonder which goes beyond the intrigue produced through the hustle, bustle, and flows of the contemporary city. The fact that the Chinese people appear to use all spaces of the public realm for culturally specific forms of communal leisure produces a condition in which the Chinese urban landscape is also a place of joy, relaxation, cultivation, and cultural expression. These routines are performed daily and continually reinforce the relationship of culture to the physical manifestation of the public realm, the landscape.

Given the embedded nature of leisure and community, Chinese leisure in the public realm takes on unique characteristics. In no other cities in the world can one hear the crack of bullwhips in the early evening as couples practice their skills of keeping a spinning top spinning, and “as early as seven o’clock [in the morning] many groups of retired or middle-aged men and women flock to the park to dance, exercise, sing, make music or meditate.”29 The types of leisure activities that people take on in China and practice in the parks, streets, and plazas of the city are almost beyond imagining, and inevitably one always comes across a strange, new, and often comical form ‘life nurturing’ or self-cultivation.

Yangsheng [养生] or ‘nurturing life’ is broadly made up of a range of self-care practices that have become popular among retirees in recent decades, but are deeply embedded in Chinese metaphysics and cosmology. Nurturing life ‘hinges almost entirely in the quotidian’, as Farquhar and Zhang argue, and includes everyday park activities such as dancing, writing, qigong and fan dancing.30