Waste Scapes: Design and Waste Crisis

April 29, 2024

Today, we are sharing an excerpt from Dan Gass’ talk ‘WASTE SCAPE’. Dan is one of the founders of BAM, an architect, and a writer. He was recently invited by LEAF (Landscape Environment Advancement Foundation), a leading landscape architecture research, education and professional discourse platform, to speak as part of their Saturday Sojourns webinar series, which engages practitioners from around the world in exploring the boundaries and applications of the landscape design profession. Dan’s talk addressed the relationship between waste and landscape, tapping into the history of the landscape architecture profession and revisiting the iconic Central Park in New York.

Transcript of Talk:

Why is waste is even remotely our responsibility as landscape architects? It is a good question. To answer that I want to go back to Frederick Law Olmsted, also known as the ‘Father of American Landscape Architecture.’ I want to revisit a project we all know, his Central Park.

What you may not know, is that the existence of Central Park, and Olmsted’s design justification for it, is a direct off shoot of the Sanitary Movement. The Sanitary Movement was a public health approach that developed in England in the 1840s to promote health and cleanliness. The agenda of this movement included building sewage systems, paving streets, providing clean water, and collecting garbage.

“Parks are now as much a part of the sanitary apparatus of a large town as aqueducts and sewers. Their management should be as much a matter of sanitary economy, and as rigidly subject to sanitary tests.” This is Olmsted’s writing in his book The Highest Value of a Park: “As the United Sates’ first great urban park, Central Park was conceived as “The Lungs of the City,” and built in 1858 as an oasis for “the sanitary advantage of breathing.”

We associate the “Natural” image of the park with our job of landscape architecture. But we should not forget Central Park’s raison d’etre: solving humble problems of urban sanitation. So, Central Park and even the foundation of landscape architecture as a profession in the United States is born out of the Sanitary Movement. Then what of our purpose?

For Landscape Architects, I question if Nature has become an end in itself. Have Naturalism, and “Design with Nature,” distracted us? We must admit that there is a contradiction here. Our Naturalism requires manuals, learned gardeners, continual maintenance. If Naturalism takes so much work to get right, are we pursuing the right idea of Nature?

Commonly, when we say we ‘love Nature’, we mean idealized wilderness. We take out the asteroids and earthquakes. This selective editing is a problem. When we say we can achieve ecological balance through the wisdom of Nature, we are also avoiding the dirty, violent, and disturbing parts of what Nature is.

Ecological Balance is a myth that has frustrating implications. Almost everything we do as modern people living in cities is essentially counter-Nature and thus some of us feel guilty. Waste is perhaps the guiltiest part of the ecological balance myth. In the idealized nature, waste and decay create a layer for renewal. It is a beautiful cycle. But when waste is ‘unnatural’, it cannot be accounted for in an ecological balance.

We are collectively avoiding the problem of waste to the point that we don’t see it as part of nature any longer. We avoid the problem of waste, but waste frustratingly stays with us. Rays of hope, like ‘compostable plastics’ or plastic-eating-bacteria are suspiciously funded and supported by the corporations that wish to make us feel more comfortable consuming.

The hard truth is that waste production is accelerating. There is no ecological balance that accounts for this. We must meet industrial consumption with industrial-scale waste solutions to achieve any form of stasis.

Shockingly, trash is considered by world’s governments as a “renewable resource.” That’s right, trash, an unending stream of materials and energy extracted from the earth’s crust, is a renewable resource, just like sun, wind and water are.

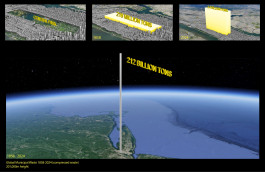

Let’s return to Central Park. Have a look at its vast size – 340 hectares. That’s about 568 soccer fields.

Now, imagine we would fill the entire area of the Central Park with compressed waste. The estimated waste the entire world produced in the year 1858, when the Central Park was built, was 219 million tons. The resulting pile is 200 meter high, enough to entirely bury the Statue of Liberty in trash.

Fast forward to 2024. The municipal waste produced globally adds up to 3.4 billion tons, to give you a sense of scale to this number, it would take over 14 thousand of world’s largest mega container ships to carry this amount of waste. Our new pile of compressed waste the size of Central Park would now tower up 3,120 meters, which is about the average depth of the Atlantic Ocean. You can see how tiny the world-famous skyscrapers became in comparison to this massive amount of waste.

Those piles were for single years. If we want to look at all waste produced in the 166 years since Central Park was constructed until today, the waste pile would tower into the thermosphere. At 201,000 meters high, it is tall enough to be a staircase from Earth’s surface to the International Space Station.

This simple math shows the titanic scale of the waste problem the humanity exists with whether we choose to close our eyes to it or not. This problem of waste will not be solved in isolated efforts. It will not be solved by quixotic landscape architects, nor will it be solved by sanitation engineers alone. However, I hope this encourages the landscape architects worldwide to consider the roots of our profession in solving humble, and maybe dirty problems. And I sincerely hope that we can work together within the profession and across disciplines to develop noble solutions to these very worthy problems.

Waste Scapes: Design and Waste Crisis

April 29, 2024

Today, we are sharing an excerpt from Dan Gass’ talk ‘WASTE SCAPE’. Dan is one of the founders of BAM, an architect, and a writer. He was recently invited by LEAF (Landscape Environment Advancement Foundation), a leading landscape architecture research, education and professional discourse platform, to speak as part of their Saturday Sojourns webinar series, which engages practitioners from around the world in exploring the boundaries and applications of the landscape design profession. Dan’s talk addressed the relationship between waste and landscape, tapping into the history of the landscape architecture profession and revisiting the iconic Central Park in New York.

Transcript of Talk:

Why is waste is even remotely our responsibility as landscape architects? It is a good question. To answer that I want to go back to Frederick Law Olmsted, also known as the ‘Father of American Landscape Architecture.’ I want to revisit a project we all know, his Central Park.

What you may not know, is that the existence of Central Park, and Olmsted’s design justification for it, is a direct off shoot of the Sanitary Movement. The Sanitary Movement was a public health approach that developed in England in the 1840s to promote health and cleanliness. The agenda of this movement included building sewage systems, paving streets, providing clean water, and collecting garbage.

“Parks are now as much a part of the sanitary apparatus of a large town as aqueducts and sewers. Their management should be as much a matter of sanitary economy, and as rigidly subject to sanitary tests.” This is Olmsted’s writing in his book The Highest Value of a Park: “As the United Sates’ first great urban park, Central Park was conceived as “The Lungs of the City,” and built in 1858 as an oasis for “the sanitary advantage of breathing.”

We associate the “Natural” image of the park with our job of landscape architecture. But we should not forget Central Park’s raison d’etre: solving humble problems of urban sanitation. So, Central Park and even the foundation of landscape architecture as a profession in the United States is born out of the Sanitary Movement. Then what of our purpose?

For Landscape Architects, I question if Nature has become an end in itself. Have Naturalism, and “Design with Nature,” distracted us? We must admit that there is a contradiction here. Our Naturalism requires manuals, learned gardeners, continual maintenance. If Naturalism takes so much work to get right, are we pursuing the right idea of Nature?

Commonly, when we say we ‘love Nature’, we mean idealized wilderness. We take out the asteroids and earthquakes. This selective editing is a problem. When we say we can achieve ecological balance through the wisdom of Nature, we are also avoiding the dirty, violent, and disturbing parts of what Nature is.

Ecological Balance is a myth that has frustrating implications. Almost everything we do as modern people living in cities is essentially counter-Nature and thus some of us feel guilty. Waste is perhaps the guiltiest part of the ecological balance myth. In the idealized nature, waste and decay create a layer for renewal. It is a beautiful cycle. But when waste is ‘unnatural’, it cannot be accounted for in an ecological balance.

We are collectively avoiding the problem of waste to the point that we don’t see it as part of nature any longer. We avoid the problem of waste, but waste frustratingly stays with us. Rays of hope, like ‘compostable plastics’ or plastic-eating-bacteria are suspiciously funded and supported by the corporations that wish to make us feel more comfortable consuming.

The hard truth is that waste production is accelerating. There is no ecological balance that accounts for this. We must meet industrial consumption with industrial-scale waste solutions to achieve any form of stasis.

Shockingly, trash is considered by world’s governments as a “renewable resource.” That’s right, trash, an unending stream of materials and energy extracted from the earth’s crust, is a renewable resource, just like sun, wind and water are.

Let’s return to Central Park. Have a look at its vast size – 340 hectares. That’s about 568 soccer fields.

Now, imagine we would fill the entire area of the Central Park with compressed waste. The estimated waste the entire world produced in the year 1858, when the Central Park was built, was 219 million tons. The resulting pile is 200 meter high, enough to entirely bury the Statue of Liberty in trash.

Fast forward to 2024. The municipal waste produced globally adds up to 3.4 billion tons, to give you a sense of scale to this number, it would take over 14 thousand of world’s largest mega container ships to carry this amount of waste. Our new pile of compressed waste the size of Central Park would now tower up 3,120 meters, which is about the average depth of the Atlantic Ocean. You can see how tiny the world-famous skyscrapers became in comparison to this massive amount of waste.

Those piles were for single years. If we want to look at all waste produced in the 166 years since Central Park was constructed until today, the waste pile would tower into the thermosphere. At 201,000 meters high, it is tall enough to be a staircase from Earth’s surface to the International Space Station.

This simple math shows the titanic scale of the waste problem the humanity exists with whether we choose to close our eyes to it or not. This problem of waste will not be solved in isolated efforts. It will not be solved by quixotic landscape architects, nor will it be solved by sanitation engineers alone. However, I hope this encourages the landscape architects worldwide to consider the roots of our profession in solving humble, and maybe dirty problems. And I sincerely hope that we can work together within the profession and across disciplines to develop noble solutions to these very worthy problems.