Annalisa Metta for Paysage Topscape Magazine: “In the Bombastic Excesses of BAM’s Geometries, We Read a More Than Topical Trace”

June 01, 2023

BUY HERE

Paysage Topscape Magazine 56, 2024, Italy.

By Annalisa Metta.

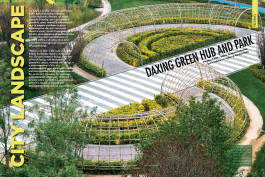

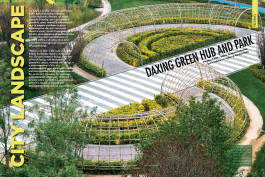

“Nature is an idea” is the motto of the BAM – Ballistic Architecture Machine architectural firm. The park created in Beijing, in the new district of Daxing, with its triumph of geometries, colours, materials and settings, is a project-manifesto of this: a phantasmagorical park which, with its skillful and ironic excesses, recalls the importance of the garden as a laboratory for landscape experimentation, where every distinction between nature and artifice is dissolved and where it is possible to intercept and interrogate the imaginaries of one’s time.

Steep hills that wind in whirling spirals, circular squares concatenated with concentric patterns of two-coloured bands, trees that seem to sprout from ceramic planes, huge exuding stone spheres, metal pergolas in vivid colours, mosaic walls with stories of contention between moon and clouds, theatres of greenery, labyrinths of hedges modelled in topiary art, theories of cones of step markers covered in yellow trecandis: these are just some of the elements of the rich phantasmagoria of the park opening in Beijing in 2019, designed by BAM – Ballistic Architecture Machine. The China based american firm is no newcomer to solutions of this kind; on the contrary, its projects are distinguished by the exuberance of signs, materials and colours, now the hallmark of an established body of work in terms of quantity and importance, as well as numerous international awards. Here, the theme is the design of a park for public use, located in the centre of a new district in the newly created Daxing district, halfway between the new airport and the more central areas of the city, on a total extension of over 15 hectares.

The initial investment is shared by the developer with some assistance from the government, the aim is to create a new destination that will attract visitors and investors. The project, in fact, pursues the goal of creating a destination that is attractive to a much wider public than just the inhabitants of the wealthy apartment blocks or the employees of the offices that overlook it, thanks also to the presence, underground, of one of the most important intermodal transport nodes in the area. The project’s flashiness and the great variety of situations and settings it proposes, in fact taking on the register of a theme park or tourist attraction, is also due to this intention. The imaginary reference on which it is built – and to which the authors explicitly refer – is the oriental garden tradition, simplified and typified, with wit and irony, in a vocabulary of geometries and essential elements, where circular shapes, mineral surfaces, isolated stones, combing of the paving that evokes in a didactic way the striations impressed on the gravel of the karensasui prevail. It is a deliberately pop interpretation of a canonised repertoire, which here meets the needs of an urban park, linked to leisure, recreation and play: ping-pong or chess tables coexist side by side with installations that evoke cosmic allegories, with a high symbolic rate. It therefore seems as if we have gone back to the 1980s and 1990s, when the pop key became the language of an entire generation of authors who played with the tradition of the garden with wisdom and humour, having the merit, among others, of having celebrated with lightness, and with a smile, the exhaustion of the stylistic options that still stubbornly persisted, thus opening the way to the new season of contemporary landscape gardening and its new expressiveness. Instead, strolling through BAM’s park in Daxing, one finds oneself in a kaleidoscope of inventions reminiscent of the early works of Martha Schwartz or Peter Walker, authors with whom BAM also collaborated. Everywhere the park is dominated by an optical weave that becomes a graphic obsession and pervades all the elements of the project: the paving, the vertical wall coverings, even the barks of the trees, which are painted in a sequence of two-tone bands. The impression at first glance is one of déjà-vu, of a citationism out of its time, with declinations that sometimes indulge in kitsch, a category that has recently returned to resonate in the debate on contemporary design. And yet, in the bombastic excesses of BAM’s geometries, we read a more than topical trace: the mockery, literally, of the obstinacy with which we would still like to distinguish between nature and artifice, tracing in the garden the matrix of an overcoming of the dichotomy that perhaps we sometimes forget, concentrated as we are today, sometimes ideologically, on environmental themes of an exquisitely performance-oriented nature. “Nature is an idea!” is BAM’s motto that stands out everywhere in the firm: nature is an idea, it is our projection; the holding of distinctions between natural and artificial is

our artificial invention.

The motto resonates, metaphorically, in this park as well, and takes on the register of a riot of excess, of a fantastic imagery, of a post-modern fairy-tale setting, in a project-manifesto that plays with us and our reassuring ethical and aesthetic convictions. The properly environmental aspects, which are imperative for the design of a contemporary park, are taken care of and satisfied by the project, which provides shady spaces for the summer heat, makes a careful selection of the botanical palette appropriate to the maintenance conditions that can be guaranteed, takes care of the regimentation of rainwater, collected and treated for recovery for irrigation purposes, and so on. But these issues do not exhaust the scope of the project, which is not resolved by respecting the mandate of sustainability, rather it incorporates it and at the same time surpasses it, since the objective of this park is to offer its visitors a memorable experience, like a landscape exhilaration, an over-excitement in strong and intentional contrast to the anaesthetic images typical of the zealous application of the “Nature-Based Solutions” manual, often prevalent in current design.

The intention here is not to argue that projects such as these should become a reference in linguistic terms to which to look for the construction of the contemporary landscape imagery, but rather to emphasise their courageous abrasive value, not at all reassuring, their subtly perturbing way of urging us to take a position on the expressive status of the landscape of our time and on the level of experimentation that it is still capable of expressing, that we are all still able to demand and expect.

Annalisa Metta is a Professor of Landscape Architecture at Roma Tre University and 2017 Italian Fellow in Landscape Architecture at the American Academy in Rome.

Annalisa Metta for Paysage Topscape Magazine: “In the Bombastic Excesses of BAM’s Geometries, We Read a More Than Topical Trace”

June 01, 2023

BUY HERE

Paysage Topscape Magazine 56, 2024, Italy.

By Annalisa Metta.

“Nature is an idea” is the motto of the BAM – Ballistic Architecture Machine architectural firm. The park created in Beijing, in the new district of Daxing, with its triumph of geometries, colours, materials and settings, is a project-manifesto of this: a phantasmagorical park which, with its skillful and ironic excesses, recalls the importance of the garden as a laboratory for landscape experimentation, where every distinction between nature and artifice is dissolved and where it is possible to intercept and interrogate the imaginaries of one’s time.

Steep hills that wind in whirling spirals, circular squares concatenated with concentric patterns of two-coloured bands, trees that seem to sprout from ceramic planes, huge exuding stone spheres, metal pergolas in vivid colours, mosaic walls with stories of contention between moon and clouds, theatres of greenery, labyrinths of hedges modelled in topiary art, theories of cones of step markers covered in yellow trecandis: these are just some of the elements of the rich phantasmagoria of the park opening in Beijing in 2019, designed by BAM – Ballistic Architecture Machine. The China based american firm is no newcomer to solutions of this kind; on the contrary, its projects are distinguished by the exuberance of signs, materials and colours, now the hallmark of an established body of work in terms of quantity and importance, as well as numerous international awards. Here, the theme is the design of a park for public use, located in the centre of a new district in the newly created Daxing district, halfway between the new airport and the more central areas of the city, on a total extension of over 15 hectares.

The initial investment is shared by the developer with some assistance from the government, the aim is to create a new destination that will attract visitors and investors. The project, in fact, pursues the goal of creating a destination that is attractive to a much wider public than just the inhabitants of the wealthy apartment blocks or the employees of the offices that overlook it, thanks also to the presence, underground, of one of the most important intermodal transport nodes in the area. The project’s flashiness and the great variety of situations and settings it proposes, in fact taking on the register of a theme park or tourist attraction, is also due to this intention. The imaginary reference on which it is built – and to which the authors explicitly refer – is the oriental garden tradition, simplified and typified, with wit and irony, in a vocabulary of geometries and essential elements, where circular shapes, mineral surfaces, isolated stones, combing of the paving that evokes in a didactic way the striations impressed on the gravel of the karensasui prevail. It is a deliberately pop interpretation of a canonised repertoire, which here meets the needs of an urban park, linked to leisure, recreation and play: ping-pong or chess tables coexist side by side with installations that evoke cosmic allegories, with a high symbolic rate. It therefore seems as if we have gone back to the 1980s and 1990s, when the pop key became the language of an entire generation of authors who played with the tradition of the garden with wisdom and humour, having the merit, among others, of having celebrated with lightness, and with a smile, the exhaustion of the stylistic options that still stubbornly persisted, thus opening the way to the new season of contemporary landscape gardening and its new expressiveness. Instead, strolling through BAM’s park in Daxing, one finds oneself in a kaleidoscope of inventions reminiscent of the early works of Martha Schwartz or Peter Walker, authors with whom BAM also collaborated. Everywhere the park is dominated by an optical weave that becomes a graphic obsession and pervades all the elements of the project: the paving, the vertical wall coverings, even the barks of the trees, which are painted in a sequence of two-tone bands. The impression at first glance is one of déjà-vu, of a citationism out of its time, with declinations that sometimes indulge in kitsch, a category that has recently returned to resonate in the debate on contemporary design. And yet, in the bombastic excesses of BAM’s geometries, we read a more than topical trace: the mockery, literally, of the obstinacy with which we would still like to distinguish between nature and artifice, tracing in the garden the matrix of an overcoming of the dichotomy that perhaps we sometimes forget, concentrated as we are today, sometimes ideologically, on environmental themes of an exquisitely performance-oriented nature. “Nature is an idea!” is BAM’s motto that stands out everywhere in the firm: nature is an idea, it is our projection; the holding of distinctions between natural and artificial is

our artificial invention.

The motto resonates, metaphorically, in this park as well, and takes on the register of a riot of excess, of a fantastic imagery, of a post-modern fairy-tale setting, in a project-manifesto that plays with us and our reassuring ethical and aesthetic convictions. The properly environmental aspects, which are imperative for the design of a contemporary park, are taken care of and satisfied by the project, which provides shady spaces for the summer heat, makes a careful selection of the botanical palette appropriate to the maintenance conditions that can be guaranteed, takes care of the regimentation of rainwater, collected and treated for recovery for irrigation purposes, and so on. But these issues do not exhaust the scope of the project, which is not resolved by respecting the mandate of sustainability, rather it incorporates it and at the same time surpasses it, since the objective of this park is to offer its visitors a memorable experience, like a landscape exhilaration, an over-excitement in strong and intentional contrast to the anaesthetic images typical of the zealous application of the “Nature-Based Solutions” manual, often prevalent in current design.

The intention here is not to argue that projects such as these should become a reference in linguistic terms to which to look for the construction of the contemporary landscape imagery, but rather to emphasise their courageous abrasive value, not at all reassuring, their subtly perturbing way of urging us to take a position on the expressive status of the landscape of our time and on the level of experimentation that it is still capable of expressing, that we are all still able to demand and expect.

Annalisa Metta is a Professor of Landscape Architecture at Roma Tre University and 2017 Italian Fellow in Landscape Architecture at the American Academy in Rome.